The Land Rent Tax and Real-Time Georgism

A Framework for Bootstrapping Land Reform from Small Scales

Henry George is probably best known for the Land Value Tax. But given his views on the nature of production, he should perhaps also be known for its dual, the Land Rent Tax. While the LVT assesses and taxes land value, the LRT assesses and taxes land rent. Both taxes effectively capture land rent that belongs to the community for the benefit of the community and are functionally almost identical. But thinking with the LRT better illuminates how to apply Georgism in real-time on small spatial and temporal scales. These small-scale implementations can incrementally bootstrap land reform.

Continuous Flows vs Discrete Quantities of Value

In Progress and Poverty, George posits that the production of wealth is a continuous process that occurs over time. A ship, he explains, is not constructed in one instantaneous act of labor, but is worked into a valuable form over time. Wages, which are the reward for labor, and rents, which toll the use of valuable resources, are thus also continuous over time. This reflects the continuous nature of production, and the recurring value that labor derives from scarce resources. Wages and rents are both continuous flows of value, taking on rates such as $20/hour or $1500/month.

Land value, on the other hand, is not continuous. It is a discrete quantity of value, such as $100,000. It is the cumulative amount of value that can be obtained from land rent over a future time horizon. An analogy is how speed multiplied by time gives the distance that would covered by traveling at that speed over that duration of time. Land rent multiplied by time equals land value.

When buying a home, for example, a family considers how much ongoing value the home would provide to them — the amount of wages they would be able to earn in the location and thus the amount of rent they would be able to pay to live there. Their wages would be earned over the finite duration of their professional careers, so the total home value they can pay for is the rent they can pay multiplied by this future time horizon. To complete the purchase, they loan money from a bank to pay for the entire home value up front, then pay off the loan over time like rent. You could say that the bank actually bought the home and rents it to the family for a few decades at a predetermined rate and duration (and collects interest in the process). The rental rate and duration of time over which the family can labor are the actual determinants of the land value.

LVT vs LRT

When a land tax is levied, it increases the financial obligation by the land owner to society for holding that land. This reduces the amount of land rent the owner is able to take for themselves. If half the land rent is captured by the tax, then the accumulated value of that land to a buyer over their future time horizon is likewise halved, and the amount they would be able to pay up-front for the land is halved. The family purchasing a home would only be able to pay half the amount for each mortgage installment since the other half of the land rent they can earn in that location is taxed, so they would only be able to buy the house at half the original price. In the distance analogy, halving speed for the same time results in half the distance traveled. The land tax reduces the rate at which the owner accumulates value from the land.

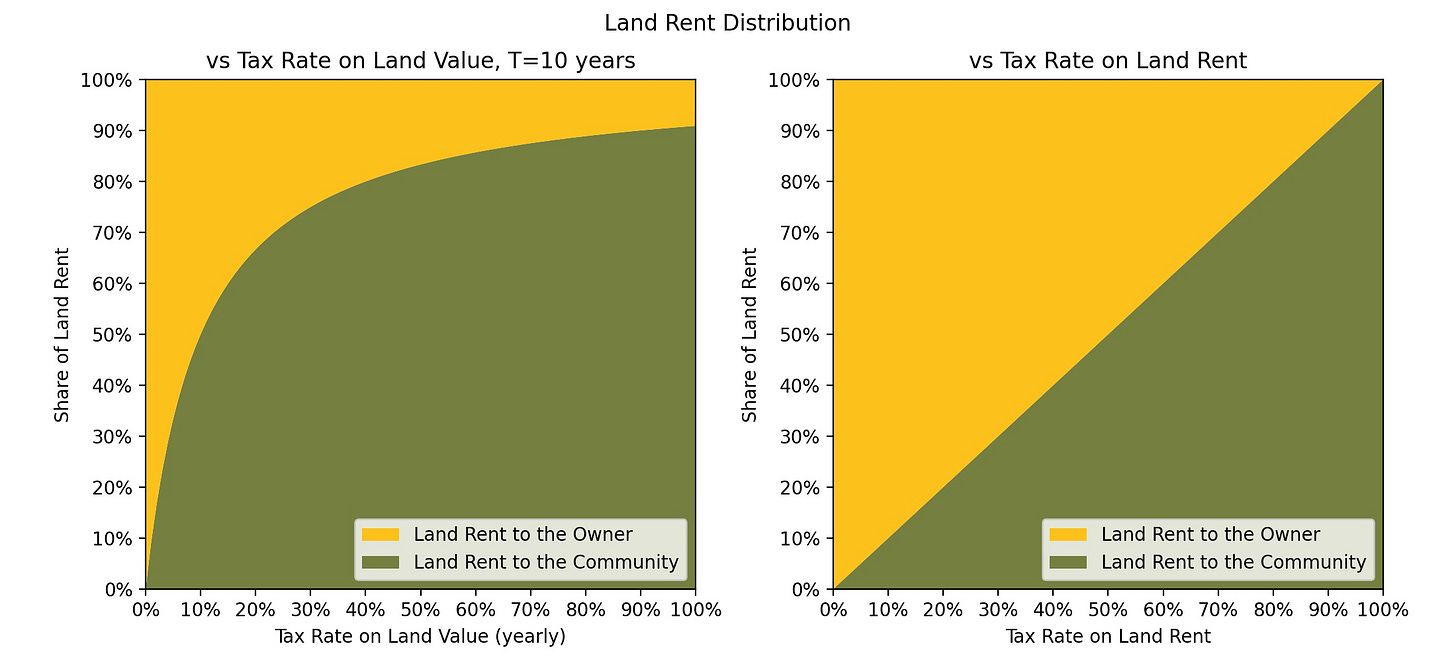

The oddity of the Land Value Tax is that it is not just proportional to the land rent, but proportional to the landowner’s definition of land value. This land value is the amount of after-tax land rent multiplied by the landowner’s time horizon. This depends non-linearly on the tax rate itself. Changing the rate of the tax on land value changes the after-tax land rent, which changes the land value. When taxed at a higher rate, land value decreases, but by how much? This is a confusing interdependence, and you need some math to figure out the solution.

On the other hand, a tax on land rent is not proportional to the after-tax value of monopolizing the resource over a future time horizon, but to the continuous flow of value that the community and nature creates in that land. This total land rent does not depend on the tax rate. Taxing it simply captures a definite fraction of the total land rent for use by the community.

In George’s perspective, land value is itself harmful to society. It forces productive uses of land to pay up-front for the future value of using the land, making productive land use expensive and precarious. Buyers assume all the risk for any potential decrease in land rent and land value that could cause their mortgage liability to exceed their income and result in negative equity. Land values also enable speculation by rewarding unproductive land monopoly for community-created increases in land rent. These effects of land value dramatically reduce the efficiency of land allocation to productive uses. In the Georgist ideal, all land rents would be captured for the community and the land would have no monopoly value to the owner. In light of this, it is odd to use the LVT to define land taxes in terms of land value when land value shouldn’t exist in the first place.

Unlike land value, land rent is beneficial to society. It is the amount of recurring natural and community value that is inherent in the land. Higher land rent means the land has greater productive advantages and can support a higher rate of wealth creation. Land rent can be increased by improving public goods — governance, education, jobs, cultural amenities, transportation, utilities, etc — anything that makes the land a more valuable place to be. This can be achieved simply by better allocating land to productive and not unproductive uses. The LRT frames the task in a way that harmonizes both the goal of maximizing the community’s fraction of the land rent, and the goal of maximizing the total land rent.

George was just as positive towards recognizing land rent as belonging to the community as he was negative towards its unjust capture by private individuals. He reconciled the tension between the individual and the collective by distinguishing the two, and called for each to justly receive the value that each deserves. It is from this positive view of the respective value of both the individual and the collective that the negative view of monopoly arises, since monopoly appropriates for private individuals that value which rightfully belongs to everyone.

Embodying the anti-monopoly view, the LVT says: “This here — this land value — is the symptom and instrument of unjust land monopoly, and it should taxed out of existence.” On the other hand, the LRT says: “This here — this land rent — is natural and community-created value that should be captured for the benefit of the community.” They are dual statements of the same problem.

But where the LRT perspective is most powerful is in understanding real-time Georgism.

Real-Time Rent Capture

When we use the LRT, we free ourselves from the challenges of thinking about land value that is accumulated over time. We don’t have to worry about buyer time horizons or account for uncertainty about future land rent. We instead see land rent as a continuous flow of value that the community creates in the land and that should be captured for the benefit of the community continuously. When we do this, we can track short-term variations in rental value, and encourage efficient land use on short timescales and on small physical scales.

For example, consider a market with too little space for all the vendors that want to sell there for the day. The limited space for stalls might be claimed by first-comers using a first-in-time ownership story, and monopolized for the whole day. Coming early to claim the best spots before others is rewarded, even if it means waiting around unproductively for customers to start showing up.

The trouble is that the value of stall space changes over a short timescale, on an hourly or minutely basis. This value is primarily determined by the busyness of the market. When it is early in the morning and quiet, there are fewer customers to sell things to and it is less valuable for a vendor to be there. When it is busier, there are more people to sell to and it is more valuable for a vendor to access this stronger customer base. This value materializes as a location rent that is captured by first-comers, just like how rising land rents benefit existing landowners and speculators.

If we dynamically price the stalls to capture this land rent and its variation over the day, then we can better encourage productive use of the limited stall space. Vendors that come when the market is not busy would pay less to access the location, and vendors that use space when the market is busy would pay more, reflecting the difference in value of using the space at different times. Those that occupy space would have to pay at least as much as anyone else would to occupy the same space. By adjusting the rent to a competitive rate, vendors are encouraged to use their space as productively as any other vendor would. Higher rents are supported by business models that better capture customer spending and are of greater total value to customers. The vendors that are most able to pay higher rents to access the market would be able to get space by pricing out less valuable space uses.

Everyone collectively negotiates for space and avoids the waste and inefficiency of space monopoly. Those that sell out of goods are encouraged by the rent to vacate their stall quickly and make room for another vendor. Vendors can choose if they want to be at the market when it is quiet and rents and sales are low, or when it is busy and rents and sales are high. Everyone fairly competes for space according to the market rate for it.

While rent should change quickly enough to capture the variation in space value throughout the day, it’s important to make sure it doesn’t change too quickly. Setting up and tearing down a stall requires labor and time. Vendors need some degree of certainty about future rent so they can foresee when someone else values the space more than they do and leave the stall before the rent gets too high. To do this, the rate of growth of rent is capped to limit abrupt increases in rent while still allowing the rent to track larger daily variations. Thus the rent the vendors actually pay would somewhat lag behind the community’s valuation of the space. We can also set the rate of change to track variations on slower timescales too, for other space uses that rely on greater future certainly on the basis of days, months, or years. Whichever timescale results in the highest net land rents would be used. Despite this lag, the rent that is captured can be captured and redistributed in real-time, second-by-second, and this has further productivity benefits.

Real-Time Rent Sharing

Real-time rent capture is a lot like congestion pricing for the use of space. Now we need to figure out how these rents should be distributed. Who is is owed the rents that vendors pay to access the market? As we saw before, it is the size of the customer base — the real-time population of the market — that gives the location value. And so it is to the people who are actively in the market that rents should be shared in real-time. This extends the Georgist policy of the Citizen’s Dividend to a real-time context.

If there are fewer people at the market, each person gets a larger share of the rents, increasing their buying power while incentivizing more people to come when customers are most needed. When there’s lots of people, the per-person rent share is naturally reduced because it is split over a larger population.

This incentive is the reverse of congestion pricing. Instead of having people pay to enter the market when it is busy, people get paid for coming to the market when it is less busy. This encourages the market to be busier at off-peak hours, distributing demand across a wider range of times and increasing the market’s average productivity. High population makes the market more productive, and real-time rent sharing directly incentivizes high population across all times of day.

Real-time rent sharing closes the feedback loop of the rent cycle. People create value, and this value attaches to the locations where they congregate, like markets and cities. Because of this, it is usually captured by location owners who demand economic rents for the location’s use. But by taxing location rent away from owners we can recover this value for the community, redistributing it back to the population that actually creates the rental value and encouraging higher productivity.

An essential benefit of this system is that it has a clean boundary with the outside world. We have a clearly-defined region where location rents are captured and redistributed. This simultaneously encourages efficient use of the limited space in the location and encourages more people to come to the location and make it valuable. This spurs productivity and location value to exceed that of other land, even when the location is small.

It is worth lingering a moment longer on why it makes sense to distribute location rents as a direct cash dividend. In our highly developed civilization, the most valuable natural opportunity of all is the right to occupy space close to other humans. Proximity to people enables low transaction costs between labors, which enables labor specialization since transactions are how everyone can access a diversity of goods while being so individually specialized. Labor specialization then enables greater individual productivity with the development of domain-specific knowledge and tools. This results in average per-person productivity increasing with population density and population size. In the U.S., productivity increases 11% with every doubling of city population. Human productivity depends greatly on proximity to other humans, and this is why the world’s most valuable land and highest land rents are overwhelmingly concentrated within dense urban cores. Land rent that is determined by population density is most naturally redistributed to the people.

Implementation

Real-time rent sharing is not something that would have been easy to implement in George’s time. It would have been extremely difficult to constantly track changes in rental value, who all is present at the location, collects the rents, and redistribute them. In the late 1800’s, a federal land value tax had clear appeal from an implementation perspective. The country has a well-defined border and population, and land value changes on this large scale are slow, so labor-intensive assessments would only need to be done occasionally. Real-time Georgism couldn’t easily exist back then.

Thankfully, we get to live in the future. We can enable anyone to bid on, reserve, and pay for the use of space with an app on their phone. We can automatically track when people enter and exit the location so they earn their share of the rents while they are there. We can design a real-time rent capture and redistribution system that operates with almost no human labor. If Henry George had the tools we have now, there’s reason to believe that he would have advocated for real-time rent sharing.

Tracking entries and exits is perhaps where the most hardware is required. We need something that logs when people enter and exit, and is difficult to cheat. We don’t want people to fool the system into thinking that they entered the location without actually entering, since they would unfairly earn a share of the location rents. We also don’t want people to leave the location but trick the system into thinking they hadn’t left.

These requirements are already fulfilled by automatic fare validation gates, used in transportation systems around the world. When entering a station, the gate ensures the passenger has a valid ticket and allows only that single passenger through. When leaving, the gate checks that the passenger got off at the right stop and that they actually left through the gate.

NFC cards and the same functions on phones can be used to track entries and exits, accrue a share of the location rents, and pay for goods and services in the location.

In a transit system, people pay to enter the station. In our system, people get paid for entering and staying in the location, so inside and outside are swapped, but everything else is the same.

The transit system gates:

only let people enter if they tap their card

only let people tap their card if they leave

The gates in our location:

only let people leave if they tap their card

only let people tap their card if they enter

We must also pick a method to value and adjust rents. Broadly, our choices are 1) assessment by an authority using a mathematical model of rental value informed by data, 2) short-term leases where the space is auctioned to and valued by the community regularly, 3) short-term leases that can be extended, albeit for a recurring increase in rent to encourage regular auctions, 4) Harberger taxes, and 5) refusable Harberger taxes. All of these methods can be used to calculate land rent in similar ways to the calculation of land value. Close-to-real-time rental value just replaces cumulative-value-over-an-indefinite-future-time-horizon as the value of the land, and that is what is taxed continuously. Experimenting with different valuation methods would be good, since each has different properties and tradeoffs.

Expansion

What happens when we do all this? We make one small location efficiently allocate space to productive uses, and reward people for being there and making it valuable. This is a small effect, but the benefits of proximity and high population should nevertheless result in higher location productivity compared to similarly advantaged land. We can’t change the underlying land rent that is influenced by external forces, like the location within a larger city. But we can influence land rent on a small scale on top of this basis — the part that is due to the internal increase in resource allocation efficiency, higher population, and greater productivity. We simply give back to people the value their presence creates, as captured by location rents, and encourage them to be productive and create value at our location instead of elsewhere.

Since nearly all locations do not have any kind of real-time rent sharing like this, people are going to be very sensitive to a small amount of rent sharing. With limited space for an initial community, the location may very well reach population capacity before rents are fully distributed at peak times. Rent will have to be put to other uses to avoid overcrowding. Because real-time rent sharing is rare, high population and high productivity will likely be induced with only a fraction of the total rents that are captured.

One good use of this surplus is payment of the loan that was used to finance the land purchase. Most of the rent would initially go to this since external influences on land rent would dominate, and would have made the initial land purchase more costly. But real-time rent sharing would increase productivity above this external land rent basis, leaving additional rent to distribute or put towards another use if it cannot be distributed.

Another good use for this rent surplus is expansion of the space available and absorption of more of the surrounding city into the community. When demand for the community’s economic opportunities exceeds its capacity for people, the best use of rents is growth and expansion to accommodate that demand.

Over time, the community may eventually become a city within a city — a special economic zone that is highly productive, and to which people are drawn more strongly than anywhere else. In a traditional city, landowners extract nearly all the value people create by being there. A Georgist city would give this value back to the people, as averaged over the population. This is a much better deal. A Georgist city would be much better able to attract people and grow in population than a traditional city. Since per-person productivity grows with population, the per-person rent share would also grow with population, making everyone wealthier as the city grows.

This model builds upon the idea of “proprietary communities” — associations of people within the private domain on privately-owned property. Examples of proprietary communities include hotels, apartment buildings, office buildings, malls, cruise ships, theme parks, etc. The idea of proprietary governance was pioneered by Spencer Heath, who diverged from the prevailing Georgist adherence to taxation and land reform through political means. Heath saw proprietary communities as the future of social organization and governance. A diversity of different communities would evolve, and the most successful ones would better attract people and expand their footprints.

Like the aforementioned kinds of proprietary communities, our model maintains a high degree of interoperability with surrounding society. We’re mainly just optimizing resource allocation in existing cities on small scales. Governance would be concerned with the collection and redistribution of rents and the maintenance of the commons. The degree to which the community achieves its goal would be transparently measured as the fraction of total land rent that is shared in real-time with the people. Similar communities might develop and compete with each other for people based on this metric, or combine their locations to better internalize location value. In a world where everyone is free to move and live in a location that best serves their needs, a Georgist community would have strong appeal, since it would best achieve economic justice, equality, and prosperity.

It’s nearly 150 years since Progress and Poverty was published, and Georgism still remains to be broadly adopted. Considering how recently the tools needed to implement real-time rent sharing became available, conditions are unusually opportune for a Georgist community to begin full land rent sharing on small scales today. By expanding outwards, it could significantly accelerate the transition to a just and human-centered economy. We hope you’ll join us on this journey.🔰

yeah, i've started preferring the term "land rent tax" or "a tax on land's rental value" when first describing the concept to people.

re "The oddity of the Land Value Tax is that it is not proportional to the land rent, but proportional to the landowner’s definition of land value. "

would argue that lvt is still proportiona to the land rent

a = x

or

a = b * x

or

a = b * x + c

in all cases, a is proportional to x. meaning that if x goes up, a goes up. in this case, linear porportionality.