Launching TinyLVT

Share resource rents in any context

The principle of capturing and redistributing rent has widespread applicability, even on tiny scales. Scarce resource issues arise the moment two or more people interact.

Georgists frequently identify the need to redistribute rent on large scales. They point out the fact that cities have a finite amount of land, that landlords capture most of people’s economic productivity, and that society can and should capture land rent and redistribute it. They cite evidence that doing so spurs production and investment, quashes unproductive land speculation, raises wages, and reduces systemic economic inequality. They advocate Georgism’s primary remedy, the land value tax (LVT), which is implemented via the powers of government. Hence, by countries, states, counties, and cities.

That’s where people usually think government stops. But below that there are layers upon layers of governments of a different kind: voluntary associations codified not with law but civil contracts. In many cases, these contracts are just as formalized as the laws and ordinances that prohibit arson, murder, or building duplexes in single-family neighborhoods. In other cases, these contracts are as simple as a verbal agreement between individuals. Who should get the front passenger seat of the car? “I called it first.” “I’m older, I should have it.” “Let’s flip a coin.”

These civil agreements often govern the allocation of scarce resources. Just as a land value tax redistributes land rent on large scales, the same basic principle can be applied by small communities in small contexts. If the fundamental theory of taxing land is correct—that it is socially productive to share resource rents—shouldn’t we expect that the very same benefits will arise when we tax even the smallest land-like resources?

For example, we can consider the following to be resources that are scarce from the perspective of the community that manages them:

Bedrooms in a home, when there are differences in desirability.

The use of common areas such as lounges, studies, or music rooms.

The use of washers and dryers at particular times in a shared house, dorm, or apartment building.

Desks, booths, and meeting rooms in a coworking space or office.

Bulletin board and poster space for advertising.

Plots in a community garden.

Booths at a fair.

Vendor stalls in a marketplace.

What would a rent sharing implementation for these resources look like? The land value tax is often mechanistically amorphous. At a high level, society must determine, somehow, what the rental value of the resource is, and demand this payment from the resource owners. Since the rent is redistributed back to society, the value of the resource is shared equally, even though the direct possession and use of the resource is not.

A common solution for land is to look at the selling prices and rental incomes of similar parcels to determine land value. And this works well so long as there’s an active land market, parcels are comparable, users of the land have similar demand, and appraisers have good data and statistical tools to work with.

But these assumptions can quickly fall apart for small, informally-managed community resources. The value of the front seat for any given car ride depends significantly on the attitudes of the negotiating parties regarding the seat’s value for that particular car ride. To employ statistical models for such a situation would involve significant labor while most likely still oversimplifying local conditions. From the outside, there is no oracle than can determine exactly what is in each individual’s head.

Instead, it is far more appropriate to use mechanisms which determine the resource allocation and price using to a quick negotiation. These mechanisms fall under the class of auctions.

In Progress and Poverty, Henry George wrote that a land value tax was functionally equivalent to auctioning the land:

For this simple device of placing all taxes on the value of land would be in effect putting up the land at auction to whomsoever would pay the highest rent to the state. The demand for land fixes its value, and hence, if taxes were placed so as very nearly to consume that value, the man who wished to hold land without using it would have to pay very nearly what it would be worth to anyone who wanted to use it.

George consistently affirms that it is rent, the ongoing payment for the use of a resource, which must be captured, including its future increase. We can conclude that resource auctions must be only for fixed-time possession rights, after which the land is auctioned again. It’s not sufficient to auction off very long-term or indefinite possession rights, since the value of a resource can change.1 For smaller-scale community resources, short-term tenancy already tends to be the norm.

Mechanism design research in recent decades now clearly shows the relative optimality of one particular auction design: the Simultaneous Ascending Auction (SAA)2, in which prices rise for a range of items simultaneously. It’s widely used by governments for wireless spectrum allocation, which makes it the implementation behind a what is essentially a land value tax for spectrum in many places.

To understand the SAA, we start with its simpler form: the English auction, which handles only one item at a time. In an English auction, the price for the item starts out small, and bidders make progressively higher bids for the item until only one person is left. That person wins the item at a price which is close to what the second-highest bidder would have paid, to within the size of the bid increment. This second-price payment is a useful feature of the auction, since the winner is not punished for their willingness to pay more than everyone else. They only pay what others would have paid, and this matches our understanding of what the resource value should be defined as.

The SAA is the same thing as the English auction, but for when there’s more than one item. Prices start low, and climb progressively higher for all items, until bidding activity stops. By auctioning all the items at once, bidders can shift their demand between items as they discover competition. The most desirable item can only be won by one person, so everyone but the winner of that item has to decide at some point to switch their bidding to alternate items. The same is true for the second-most desirable item, the third-most, and so on.3 By enabling many items to be auctioned, with much better results than sequential single-item auctions, the SAA makes auctions practically usable for many kinds of resource allocation problems.

In our SAA-based rent sharing implementation, the proceeds are redistributed equally to the community, including to the winners of the auction, if they count as community members. The equal distribution reflects each community member’s equal right to the resource value.

In capturing and redistributing the value of their resources, communities can achieve incentive alignment. Members get their share of the resource value whether they use it directly or not. Everyone benefits when the resource’s rental value is maximized.4

While there’s many ways to design a small-scale rent sharing system, this design has many advantages. Members participate directly in the resource pricing and allocation, rents are simply redistributed, the auction results are easy to compute, and an implementation would be easy to write in software and deploy widely.

So, to that end, I’ve been working on a project called TinyLVT to make this mechanism practically available and usable, and it’s now live at tinylvt.com.5 You can:

Create a community and invite people to it.

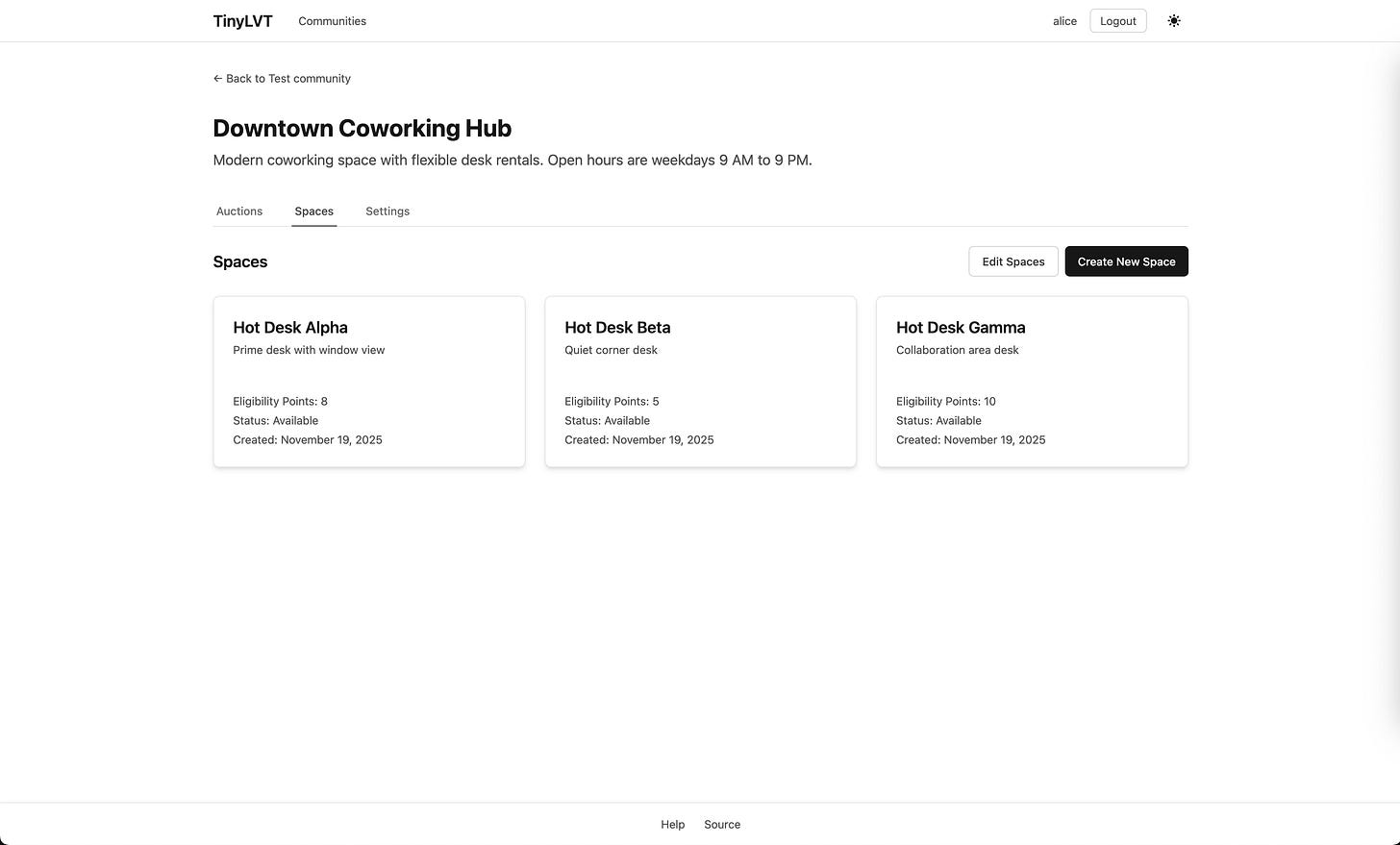

Define “sites”, which each encompass a set of “spaces” that are all auctioned together.

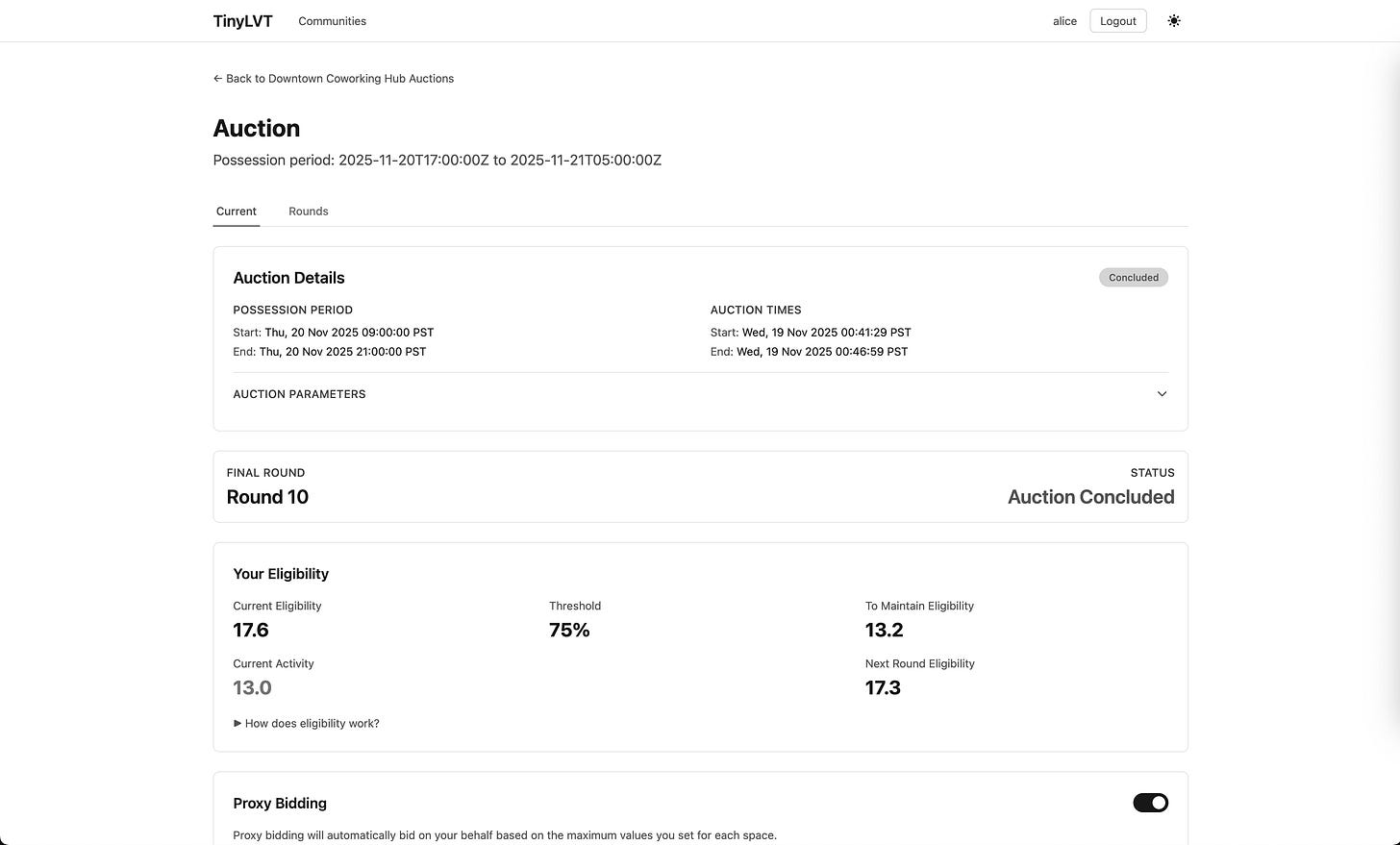

Hold Simultaneous Ascending Auctions for time-bounded space possession.

Use proxy bidding to automatically bid for the items you value most.

Space is the most common scarce resource in need of sharing, and the naming reflects this. However, the things you auction don’t have to be physical spaces.

When auctions conclude, the space winners and prices are shown. These prices are the debts winners must pay to the community—one equal fraction to each member. Soon I’ll add debt tracking between community members, which will automatically record what each winner owes to everyone else in the community for using a space. Tracking debts allows for easier, bulk settlement at a future date, when many debts can cancel out.

Furthermore, you’ll be able to define which members are eligible for receiving the rent redistribution, separate from the definition of who is eligible to bid for spaces. This is useful when you want to define rent redistribution eligibility according to presence in the community, while allowing a larger group of people to bid for space. For example, when people want to bid for spaces in advance, before being present in the community.

These future improvements aside, the core auction mechanism is functional and ready to use. If you can convince a community in your life to try out this system, then you can demonstrate the concrete benefits of rent sharing, and gain valuable insight into what it takes to deploy it. Give it a shot and share your findings!

A drawback for land is that regular auctions strictly limit the time horizon over which possessors can enjoy the value of their permanent improvements to the land. At the next auction, the value of any improvements gets absorbed into the land value, since they can be enjoyed by the next possessor of the land. However, the waste and under-investment that comes with absolute private ownership in land is in most cases far costlier than a disincentive to make permanent improvements. A city in which all privately-owned improvements were designed to be movable could still be vastly more vibrant and prosperous than the cities of today.

T. Roughgarden. Combinatorial and Wireless Spectrum Auctions. CS364A: Algorithmic Game Theory. 2013. https://timroughgarden.org/f13/l/l8.pdf.

Tim Roughgarden’s course notes for Algorithmic Game Theory and Frontiers in Mechanism Design are excellent resources on auction theory.

In the SAA it’s also important to ensure that bidders can’t wait until the end of the auction to bid, since this prevents price discovery and causes the auction to slow to a crawl. We can do this by tracking bidder “eligibility”, which requires bidders to maintain some minimum amount of bidding activity throughout the auction. Each item is assigned a certain number of eligibility points, approximately matching its estimated value. Each round, bidders must maintain some fraction of their current eligibility, or it decreases permanently. For example, in a round with a 50% eligibility requirement, a bidder with 100 points of eligibility must be the standing high bidder or actively bid for at least 50 points of items. If they have less activity, like 40 points, then their eligibility falls according to the round’s 50% requirement, resulting in a new eligibility of 80 points. Eligibility requirements can become stricter (closer to 100%) as the auction progresses.

We can even use this system to tax externalities directly. Suppose that some residents of a dorm want to hold a loud event that will disturb other residents that want to study, and who are opposed to the event. So, the house holds an auction for the outcome, with each side pooling their bids towards the outcome they want. If the event-supporters win, then they pay the community for winning the outcome, and the proceeds are redistributed equally among the residents. Those who opposed the event would, at the very least, receive compensation for being denied the outcome they wanted. If the outcome was the reverse, the payment would go the other way.

Contrast this to a majority vote. A vote grants all members an opportunity to influence the outcome. But it does nothing to rectify the loss that the minority suffers. The event-opposers, when in the minority, receive no redress for suffering the disturbance of the loud event. On the other hand, an auction with rent redistribution provides precisely this reimbursement in exactly the right amount.

The source code is hosted at https://github.com/10log10/tinylvt.